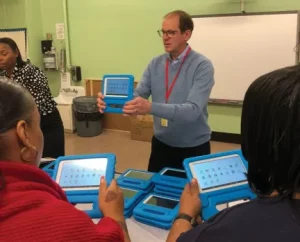

ApSeed founder, Greg Alcorn, demonstrates the Seedling to Head Start teachers in New York City

ROWAN COUNTY, NC – After starting with 60 touchpads for local Head Start students in 2016, the ApSeed program created by Salisbury entrepreneur Greg Alcorn should hit the 20,000 mark by the end of August.

That’s 20,000 devices distributed free of charge to teach at-risk preschoolers their letters, numbers and other basics expected for kindergarten readiness.

Alcorn envisions the program going statewide some day.

“You talk about raising the ceiling. We’re about to raise the floor, too,” he says.

The owner and CEO of Global Contact Services, Alcorn launched the nonprofit, ApSeed Early Childhood Education, and oversaw development of its signature touchpad, the Seedling. For years ApSeed relied on private funds from individuals and foundations, with Alcorn and wife Missie as primary donors.

Now, the initiative is in the midst of a growth spurt, thanks to $2.5 million in state funds the General Assembly OK’d last year to expand ApSeed in 2023. More state funding may come through the budget now under debate in Raleigh.

Alcorn says ApSeed has gotten good results with last year’s allocation, reaching 3- and 4-year-olds in more than the 10 counties initially targeted.

In addition to Rowan, this year the program will reach Ashe, Buncombe, Davie, Duplin, Granville, Iredell, New Hanover, Pender, Rockingham and Yadkin counties, as well as Lexington city. Head Start programs in Vance, Franklin and Warren counties are on board.

Seedlings have also been distributed in five South Carolina school districts.

ApSeed follows the same principle Alcorn has used throughout his career.

“Our business approach has always been don’t do anything unless it can scale,” Alcorn says.

“Scale means grow. … Do one thing, do it better than anybody else and do a lot of it.”

State Rep. Harry Warren, R-Rowan, has advocated for state funding.

“I’ve been impressed to see the commitment the Alcorns have made,” Warren says, “and the support they’ve received from the private sector to provide Seedlings, free of charge, to the unserved and underserved children who could benefit the most.”

Cost savings

Alcorn estimates taking the program statewide would cost $35 million to $45 million, but with a big payoff.

“I’m confident that the results we’re getting are going to translate into cost savings from the educational world,” Alcorn says.

He predicts less need for remediation or summer school and fewer discipline problems, keeping socioeconomically disadvantaged children on the same path as other students.

“That achievement gap is scary,” Alcorn says. “And preventable.”

The dream since Day One, he says, has been to prove that at-risk children who use Seedlings have better kindergarten readiness than peers who don’t. Results have been positive, he says.

In South Carolina, for example, Union County Schools’ 2022 Pre-K program reported that students who had Seedlings scored an average 75 percent on emerging readiness, while all 4-year-olds had an average of only 41 percent.

If children do well in kindergarten, Alcorn says, they’ll likely do well in first grade, and second grade and so on, and have a much better chance of proficiency by the time they take the all-important third-grade reading test.

That, Alcorn believes, will allow their schools to be seen in a more favorable light, as well as their neighborhoods, and economic development will follow. People will want to live in these communities, he says.

“So, numerically, where do we want to be in five years? Sure we want to do the whole state. It’s about 300,000 children.” Half of them would be considered of low socio-economic status — children ripe for ApSeed.

Planting Seedlings, growing learners

With colorful characters and gentle music, the Seedling’s 16 apps offer children lessons on everything from baby games to sight words and math.

Little fingers can tap on the Baby Phone to “call” selected animals and hear the moo of a cow or the grunt of a camel.

A multiplication app responds to correct answers with a cheerful “good job,” and fireworks.

But ApSeed is not just about Seedlings and apps.

ApSeed’s new executive director, Dr. Julie Morrow, is working with Alcorn to beef up the program with readiness tutors, support materials and increased methods to track the Seedlings’ use and effectiveness.

She likes the program’s motto: Planting Seedlings, growing learners.

The program is in a state of continuous improvement itself.

“We always have concerns about whether we’re doing this the very best way,” Alcorn says. The newest Seedlings are the device’s sixth version, custom made for ApSeed by a manufacturer in Hong Kong.

Earphones were added at the suggestion of a parent who grew tired of hearing the games their child played over and over. Alcorn takes that as a sign of success.

“We love it when they say, ‘Do you have anything harder?’” Alcorn says. That means children have mastered the pre-kindergarten skills in the Seedlings’ apps.

But his answer is no.

“Our swim lane is kindergarten readiness,” Alcorn says. “First grade is out of our league.”

Help for parents

With a Seedling touchpad, ApSeed now gives each child a “Readiness Kit” — a string bag full of items to help build different skills.

“We realized the Seedling teaches letters, sounds, numbers, shapes, colors,” says Morrow.

“There’s also other things kids have to do in order to be kindergarten ready.”

The kit includes:

• Colorful Unifix cubes for hands-on stacking and counting

• Flashcards on colors, numbers, letters and shapes

• A small whiteboard and marker for writing practice

• Crayons and training scissors

• A book containing a story or writing exercises

• Tip sheets for parents — in English and Spanish — on reading with their children, and listing skills expected when a child enters kindergarten

• Suggestions on 30 activities to do with simple things around the house: for example, use junk mail for cutting, practice writing with shaving cream

“I’m very excited about those kinds of opportunities,” Morrow says. It’s not that parents don’t want to teach their children basic skills, she says. “They just don’t know how to help.”

The program has made short videos in English and Spanish. Alcorn dreams of making bilingual Seedlings, too, but he’s been advised to keep the Seedling English-only because kindergarten readiness testing is done in English.

Seedlings have been distributed through preschools, Head Start centers, WIC nutrition programs, pediatricians’ offices and even community events.

In Salisbury, ApSeed gave out Seedlings and held activities during the Back to School Celebration at the Salisbury-Rowan Community Action Agency on Friday, July 21.

Dione Adkins, executive director of the agency, says Head Start students have made significant literacy, social and cognitive gains with the touchpads.

“I am overjoyed by the progress of our students and could not think of a better addition to our educational tools than an ApSeed Seedling,” she says in an online testimonial.

Word spreads

Seedlings have popped up beyond North Carolina through friends and business connections.

ApSeed entered five South Carolina school districts at the suggestion of Dr. Lynn Moody, the former Rowan-Salisbury Schools superintendent who worked in Rock Hill for several years.

Alcorn would like to take the program statewide there, too.

Alcorn’s business, Global Contact Services or GCS, operates a call center in New York City that fields transportation requests for people who are disabled. As part of GCS’ community outreach, ApSeed expanded into eight Head Start centers run by the Police Athletic League in Queens.

Salisbury Mayor Karen Alexander connected ApSeed to a school in Monrovia, Salisbury’s sister city in Liberia.

And a friend of a friend made connections for ApSeed in a Zimbabwe village. The school there sent Alcorn videos of smiling children holding Seedlings and tracing out letters in the air.

Alcorn’s inspiration

The seed for ApSeed was planted when Alcorn served on the State Board of Education. He was stunned to learn how much more a high school graduate earns than someone who drops out: $10,000 a year.

Over 40 years of work, that would amount to $400,000.

He became convinced that the most effective way to help more students earn a diploma and get that $400,000 edge was to start at the beginning with preschoolers of low socio-economic status.

The wheels were turning. With a talent for developing programs that can scale and an altruistic bent instilled by his parents — plus the feeling that, in his 60s, he had yet to reach his full potential — Alcorn decided to take on the challenge of boosting kindergarten readiness.

He says lines from a Twiddle song, “Lost in the Cold,” spoke to him about the struggles some face.

“All my burdens keep me hurtin’

“Ever present, ever certain …

“It’s hard to see the future

“When the present doesn’t suit ya”

Early intention

Morrow juggles many ApSeed duties — holding quarterly meetings with each district, pursuing grants, hiring readiness tutors to work with families in each county, improving the website, tracking equipment and expenses, and even riding a Bookmobile in Buncombe County to give out Seedlings in a mobile home park.

She shares a saying Alcorn often uses: “Passion plus productivity equals fulfilled promise.”

Kindergarten readiness is a hot topic, she says. You can’t expect slow starters to reach the same achievement level as better-prepared classmates.

“It’s harder to catch up,” Morrow says, “than being on the same starting line.”

A dollar invested in quality early childhood programs can yield returns between $4 and $16, according to research by Nobel Prize-winning economist James Heckman.

That kind of return on investment motivates Alcorn, who is pushing for generational change, generational improvement.

“If we get it early … with the early intention of being able to go and do as much as we can with those 3- and 4-year-olds to get them ready for kindergarten, then you’ll win.”